"Augustine's Angst": When One of the Church's Greatest Theologians Got Bible Translation Wrong

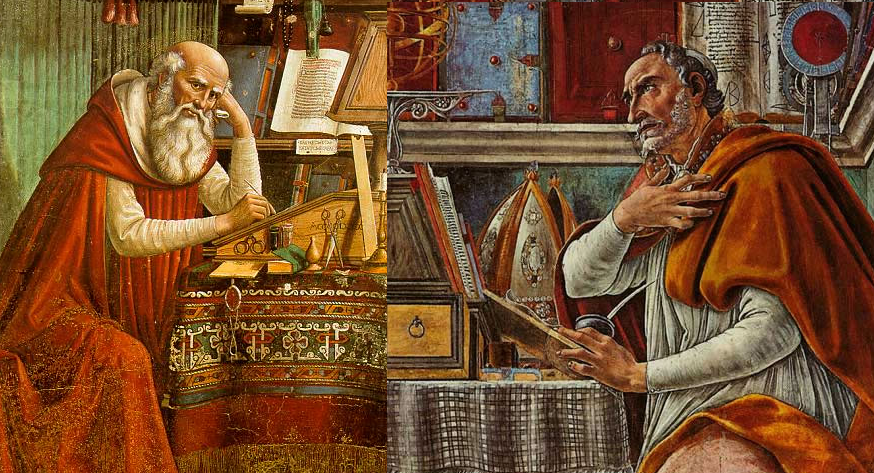

Augustine of Hippo stands tall as one of the greatest churchmen and theologians of Christian history, and he is one of my personal heroes. It is hard to express how deeply indebted to him we are today. Yet, between AD 394 and 405 he and another church luminary, Jerome, corresponded about various matters, including Augustine's concerns about Jerome's translation of the Old Testament from the Hebrew original. I think in this rare case, Augustine got it wrong.

Three Points of Context

Three points of context help us understand their discussion. First, in the earliest centuries of the Church, the primary translation of the Old Testament used by those who could read Greek (which included most of the Church) was the Septuagint, which had also been the main translation used by the first followers of Jesus (many of the quotations in the New Testament are taken from the Septuagint). So, for them, Greek was the language of the Old Testament, even though it was written originally in Hebrew.

Second, to meet the needs of Latin speakers, many people before and up to Augustine's time were doing amateurish translations of the Bible into Latin, few of them authorized by the Church and most of them very poor. Augustine said, "In the earliest days of the faith, when a Greek manuscript came into anyone's hands and he thought he possessed a little facility in both languages [i.e. Greek and Latin], he ventured to make a translation" (On Christian Doctrine, 2.16). Consequently, Jerome had been asked by a superior named Damascus to do an official Latin translation for the Church, which he completed in AD 405. This translation, which a millennium later would be dubbed "The Latin Vulgate," would become the standard translation for the "Roman" church of Western Europe and would reign as Europe's primary translation for over a thousand years. Jerome did not want to do the translation, anticipating that it would be a thankless job and that his translation would be opposed by many. He was right. (Interestingly, when the KJV was being produced, the Roman Catholic church took the position that Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, with its language of heaven, was the only appropriate translation, stating that the Bible in the vulgar English of common people was inappropriate! Do we see a pattern here?!)

Third, Augustine was a bishop in northern Africa, a Roman province where Latin was the language of choice for educated people, so he wanted a good translation of the Bible in Latin, and he was glad Jerome was producing a Latin translation. Initially Jerome translated the Old Testament from the Greek Old Testament, which made Augustine happy. The latter states, “I would, of course, prefer that you translate for us the canonical Greek scriptures . . .” Yet, Jerome found working from the Greek translation of the Old Testament unsatisfactory, switching to the Hebrew manuscripts instead. Understandably, there were places where his translation varied from the Septuagint, and this gave Augustine a great deal of angst.

Augustine’s Concerns

In their correspondence, Augustine had 3 primary reasons for objecting to Jerome's translation from the Hebrew, encouraging him, rather, to translate from the Septuagint. His reasons are interesting—and I think still with us to this day.

1. If the Septuagint was good enough for the apostles, it should be good enough for us! Augustine appealed to tradition. Speaking of the Septuagint, he writes, “that version has no small authority; it has deservedly, after all, been widely used and was used by the apostles.”

2. Second, he appealed to the pragmatic impact of Jerome’s translation, which he saw as negative, saying in essence, “Your translation is messing people up!” He writes, “I did not want your translation from the Hebrew to be read in the churches for fear that, by introducing something new opposed to the authority of the Septuagint, we might disturb the people of God to their great scandal, for their ears and hearts are accustomed to that translation that even the apostle’s approved.” Earlier in the correspondence he gives an example. A church leader in the Northern African city of Orea had tried to use Jerome’s translation of the book of Jonah. It almost started a revolt, and the church leader had to correct what Jerome’s translation had said at points or lose his church! This raised a third point.

3. Augustine argued, since a facility in Hebrew is rare, who is going to be able to judge between you and the more established Septuagint? In other words, the ability of church leaders to deal with questions related to translation was a concern, and it was a valid concern.

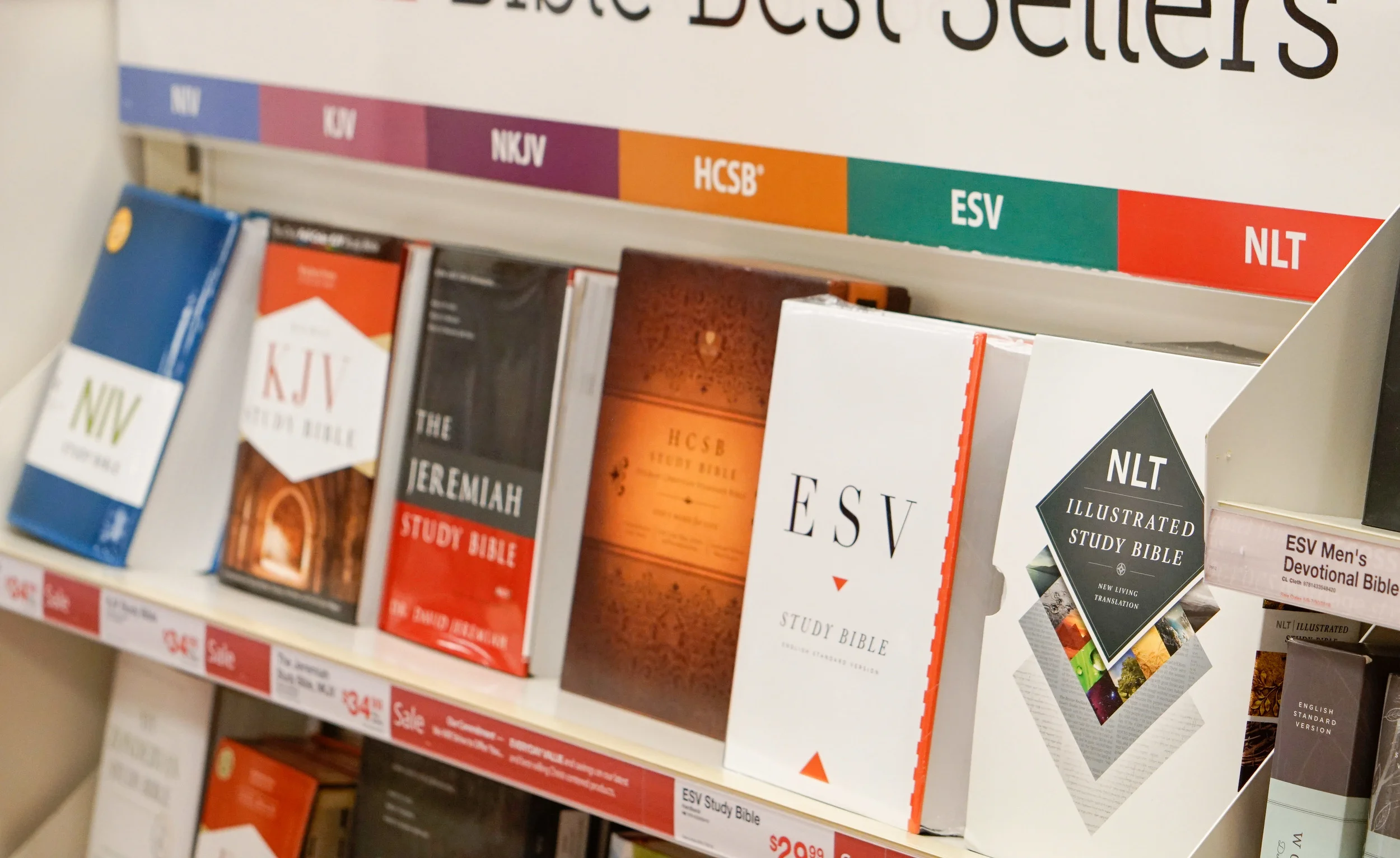

So, Augustine had a considerable amount of angst over a newfangled translation coming on the scene, and, interestingly, we hear similar arguments today, do we not? “This is not the traditional translation the church has always used!” and “Won’t people’s confidence be shaken if the new translation differs from the one we have always had?” and “Who can question the authority of the traditional translation?” So what can we say to all of this?

Where Augustine Got It Wrong

Briefly, Augustine’s first objection misses the point of translation. Translations are necessary where something new is going on, where boundaries in language and culture are being crossed by the gospel. When the church crosses language barriers, or over decades or hundreds of years a language changes, new translation is necessary, for the Scriptures should be read and heard in the heart language of people, that language they grew up speaking in their homes. And the measure of accuracy? The original languages of Hebrew and Greek, in which God gave the Word! Augustine had made a translation the standard, and that was a mistake.

Second, the practical effect of a translation, a good effect or a bad one, forms a poor foundation for judging a translation of the Bible. Sometimes adapting to what is best and most biblical for the church is painful and takes a period of education and adjustment, especially where the church has grown used to tradition trumping that which is biblical. We should not simply appeal to what works or what doesn’t. We need to probe deeply what helps people hear accurately and live the authoritative Word. On this point, beloved Augustine was simply reacting to a reaction against Jerome's better translation.

Third, Augustine's point about whether church leaders were equipped to deal with disputes about translation was appropriate. Thankfully, unlike Augustine’s day, we now have an embarrassing wealth of resources for dealing with the original languages of the Bible. Especially in English, we have sound tools galore, written by godly churchmen who can lead us in discussions on disputed points in the Bible or a translation, and they can help us to learn how to process difficult questions that come up.

Now in fairness to Augustine, the issue of Bible translation was not a bridge that large sections of the Church had had to cross. Discussions about Bible translation were new territory for many. Maybe such discussions are new for some of us as well, but they are very important.